- Home

- Cannell, Michael

Limit, The

Limit, The Read online

THE

LIMIT

ALSO BY MICHAEL CANNELL

I. M. Pei: Mandarin of Modernism

THE

LIMIT

Life and Death in Formula One’s Most Dangerous Era

MICHAEL CANNELL

First published in hardback and export trade paperback in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Michael Cannell, 2011

The moral right of Michael Cannell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 184887 222 6

Export and Airside trade paperback ISBN: 978 184887 223 3

E-book ISBN: 978 085789 419 9

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Evie and Cricket

Contents

Prologue

1. An Air of Truth

2. A Song of Twelve Cylinders

3. This Race Will Kill Us All

4. The Road to Modena

5. Pope of the North

6. Count von Crash

7. Garibaldini

8. Ten-Tenths

9. Birth of the Sharknose

10. 1961

11. Pista Magica

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

Speed provides the one genuinely modern pleasure.

—Aldous Huxley

In Morte Vita

(In Death There Is Life)

—the von Trips coat of arms

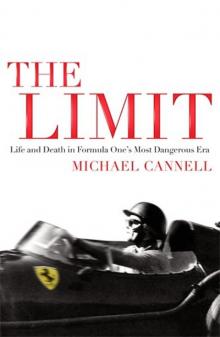

Phil Hill leads a procession of Ferraris on the notorious banking at Monza, site of the 1961 Italian Grand Prix. “This was a duel in the sun,” a correspondent wrote, “and the pace was too hot to last.” (Cahier Archive)

Prologue

THEY BEGAN ARRIVING a day in advance. The loyal Ferrari following—the tifosi—rolled up in caravans of Fiats and battered motorbikes to camp among the chestnut groves that spread more than six hundred acres around the boomerang-shaped racetrack in Monza, Italy. By the glow of evening campfires they raised cups of grappa to the great drivers, the piloti who once thundered around the terrible banked turns of the Autodromo Nazionale looming at the edge of the woods like a concrete cathedral.

Most of those piloti were gone now. Between 1957 and 1961 twenty Grand Prix drivers died. Many more suffered terrible injuries. By some estimates, drivers had a 33 percent chance of surviving. In the days before seat belts and roll bars, they were crushed, burned, and beheaded with unnerving regularity. One driver retired after winning the championship only to die three months later in an ordinary car accident near his home.

The survivors raced on, in spite of the ominously long death roll. Inside the autodromo half a dozen teams and thirty-two drivers warmed up for the 267-mile Italian Grand Prix, the climactic race of the 1961 season, with the spotlight focused squarely on Ferrari teammates Phil Hill and Count Wolfgang von Trips. The next afternoon, on Sunday, September 10, they would settle their long fight for the Grand Prix title, racing’s highest laurel. One last race remained, the U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen, New York, but Monza was expected to decide the back-and-forth battle between the two men.

Von Trips held a four-point edge, and he had earned the advantageous pole position with the fastest practice laps. His easy, agreeable manner gave him the air of an inevitable winner. He had the comportment of a champion. On the other hand, he had crashed twice at Monza over the previous five years. Either could have ended his career—or killed him. He had recovered, but the accidents clung to him like a curse. By comparison, Hill had won at Monza a year earlier, and he had set several lap records. If von Trips was the erratic star, Hill was his rock-steady complement. Like any great sports story, it was a pairing of opposites.

The two men had traded checkered flags all summer as the Grand Prix made its way through six European countries. Their contest reached manic proportions, just as Borg vs. McEnroe and Ali vs. Frazier would in the following decades. It played large on the front pages of European newspapers. “This was a duel in the sun,” the Times of London wrote on the eve of the race, “and the pace was too hot to last.”

Neither man was Italian, which suited Enzo Ferrari, the reclusive white-haired padrone of the Ferrari empire. Every time an Italian driver died the government launched a meddlesome investigation and the Vatican made thunderous condemnations.

The rivalry was made vivid by their polar personalities—the American technician versus the German nobleman, loner versus bon vivant, backstreet hot rodder versus Rhineland count. Each would be the first from his country to earn the title after the war. Each considered himself a nose faster.

The location only heightened the suspense. The Italians called Monza the Death Circuit, in part because the banked turns catapulted errant cars like cannonballs. The sloped surface was coarse and pockmarked, and it exerted a centrifugal pull the fragile Formula 1 cars were not designed to handle. (The British teams had boycotted Monza in 1960 because they judged the banking too perilous.) More dangerous still, the long straights allowed drivers to touch 180 mph, and to slipstream inches apart. A series of tight curves, known as chicanes, had been installed to slow the cars, but it was still a track to be driven flat out. As much as any racetrack in the world, it conjured racing’s heroics and horrors. To the north, it curved into a silent forest that was haunted by its many victims (or so went the legend).

The sun rose on a perfect cloudless Sunday with pennants snapping in a brisk breeze. The racetrack was bathed in soft September light. The pale outline of the Alps was visible to the north, glimpsed between a pair of Pirelli scoreboard towers. By afternoon the tifosi had gathered thirty deep at trackside railings, singing and drinking Chianti. They were jubilant in the promise of seeing the Italian cars humble the British—the hated Brits who had dominated the podiums over the previous few years with a new breed of lightweight, agile cars. Now the Italians were again ascendant, the British in retrograde. The anticipation was exceptional, even by the feverish standards of Grand Prix.

Down below, in the pits, mechanics clenching spanner wrenches and screwdrivers scurried around a fleet of low-slung single-seat cars painted national racing colors—red for Italian teams, green for Great Britain, silver for Germany—with no corporate logos to obscure them. Within a few years media handlers and sponsorship deals would inundate Grand Prix, setting it on its course to becoming the formidable business it is today, but in 1961 racing was more about nationalism than money. Though never stated explicitly, it was animated by dark, hawkish undercurrents. Ancient grudges were avenged with checkered flags. Young men died in the most advanced machinery their countries could devise, as they had in World War II.

The memories of the war, now sixteen years past, were increasingly overtaken by Cold War apprehension. Two weeks before the Monza race, Communist officials had sealed the border between East and West Berlin with concrete and barbed wire. Almost overnight it became a hair-trigger world fraught with spy planes and satellites, intercontinental H-bombs, and an emergent space race. Phil Hill recognized the sport’s ominous und

ercurrent. He and von Trips were, he said, gladiators in “an age of anxiety.” For his part, von Trips knew that the pageantry of a Grand Prix title would provide a unifying lift for his fellow Germans. Countries have a way of creating the hero they need, and von Trips fit the part.

The two men cleared their minds as mechanics rolled their red cars into formation. They lowered themselves into reclined seats made to their specifications, their legs reaching through the fuselage for pedals. Their shoulders pressed tightly against wraparound windscreens and their gloved hands clenched and unclenched small leather-padded steering wheels. Gauges jumped to life as the engines fired. Finely wrought Italian cylinders thrummed in staccato and a hornet shriek of exhaust resounded off the heaving grandstands. Smoke billowed behind them. They were alone now, each in their own world. If they went too slow they’d lose, too fast and they’d die. Within moments they would be engaged in a solitary pursuit of the sweet spot drivers called the limit.

THE LIMIT

Phil Hill after the 1950 Pebble Beach Cup, the last-to-first dash that converted him from mechanic to driver. (Pebble Beach Company)

1

An Air of Truth

PHIL HILL HATED THE DINNERS most of all. The vile dinners with his parents cursing each other across the long table in their Santa Monica dining room. Shouting, taunting, springing from their chairs and spilling wine. Hill sat in stony silence with his siblings, too shaken to touch the pot roast or fried chicken put in front of them. Even as their parents fought, the children were required to maintain perfect table manners.

It always happened the same way. In the afternoon Hill would hear the faint chime of piano keys, the major and minor chords chasing each other as his mother worked out arrangements for the hymns she composed for publication. At 5 p.m. sharp his father left his job as postmaster general of Santa Monica and drove to the Uplifters Club, a hard-drinking enclave of civic stalwarts and businessmen, where he was known for making extemporaneous political speeches over a series of whiskeys. After more drinks—sometimes a lot more—he headed home in a darkening mood.

Julia, the black cook, climbed the tiled stairs of their home on the edge of Santa Monica to tell Hill and his younger brother Jerry and sister Helen that they would eat with the grown-ups that night. They dreaded it. Their father was a devoted Roosevelt Democrat, their mother an avid Republican. Meals ended in political quarrels enflamed by booze. Later Hill would sleep with his hands covering his ears to muffle the screaming downstairs.

When Hill was fourteen his father came home drunk and hit his mother. Hill pushed between them and hit him back. “It was the first time I ever struck my father,” he said. “I had this feeling of power over him, finally. I remember it was a good feeling.”

It should have been an ideal childhood. The Hills were pillars of Santa Monica, a thriving community on the edge of Los Angeles with a palm-shaded promenade overlooking a broad beach where children swam and played ball in the California sunshine. They lived in a Spanish-style house on 20th Street with creamy stucco walls, exposed beams, and dark wood floors. Shirley Temple lived next door. It was the picture of California comfort.

The setting was no solace to Hill. He grew up wretchedly disconnected from his domineering parents and painfully unsure how to fit in to his surroundings. He was slightly built and sickly, and he stood aloof from the boys patrolling the neighborhood. When polio broke out in 1936, his mother hired a tutor to homeschool Hill and his siblings for a year. He was further confined by a sinus condition that required a tube inserted in his nose. He was too clumsy to find escape in sports. “I was awful,” he said. “When we played baseball I was always the poorest member of the team—the fact that I was cursed each time I came to bat didn’t help me play any better.” His only contentment was playing the piano. It was not just the music that captivated him, but also the reliable mechanical play of key, hammer, and damper.

His mother was too preoccupied with her own musical pursuits to pay much attention to family. She stayed up late listening to an Edison Victrola and writing hymns, including a popular song called “Jesus Is the Sweetest Name I Know.” She also wrote religious tracts refuting the claim that Prohibition had a biblical basis. By her reading of the Bible, God endorsed drinking. And drink she did. In the mornings she slept it off while a chauffeur delivered Hill and his brother to school. “Jerry and I hated to let the other kids see us,” he said. “This was during the Depression, and we felt just awful being taken to school like a couple of royal princes, complete with Buster Brown haircuts.”

Hill’s father, Philip Toll Hill Sr., was a disciplinarian with the rigid mindset of a lifelong civil servant. He came from a long line of stalwart northeastern burghers and businessmen, all of whom attended Union College in Schenectady, New York. He followed in their path, then became a navy lieutenant in World War I and city editor of the Schenectady Gazette before taking a sales job with Mack Truck in Miami, where he married Lela Long, a farm girl from Marion, Ohio, with musical ambitions.

Philip T. Hill Jr., was born on April 20, 1927. Four months later the family fled Miami as a hurricane bore down. Lela had lived through one hurricane, and she refused to face another. The family drove across the country to Los Angeles, where Hill’s father briefly worked as foreman of the L.A. Grand Jury, then became postmaster general of Santa Monica.

He was a remote figure who ruled the household with regimentation. His children addressed him as “sir.” He trained his sons to greet women with a bow and a crisp click of the heels. In 1935, he sent eight-year-old Hill to the Hollywood Military Academy. “Be a good little soldier,” his father told him. Hill was anything but soldierly. His one interest was the most unmilitary activity available: playing alto horn in the school band.

Hill found his salvation in the family garage. The story of his childhood is bright with automotive impressions—the elegant tangle of wires under the hood of his mother’s shiny Marmon Speedster; the Oldsmobile a family friend let him drive around the block, his back supported by pillows and his feet grazing the pedals; the 1928 Packard his parents drove up the coast road to Oxnard for picnics, with Hill egging his father on. “I remember going down one of those hills seeing 80 on the speedometer,” he said. “And stuff was blowing out of the car and my mother was screaming bloody murder—and I loved it.”

When Hill and some friends were driven home from a birthday party in a green 1933 Chevrolet sedan, he paid each passenger twenty-five cents for the privilege of sitting beside the driver and shifting gears. They laughed at his determination as they held out their tiny palms to collect the coins. “I was born a car nut,” he said. “Really a mental case.”

It was common for boys to fall for the full-figured cars of that era, but Hill verged on infatuation. Staring out at San Vicente Boulevard, he would challenge neighborhood boys to shout out the make and year of approaching cars faster than he did—’39 Chrysler Royal, ’40 Chevy Coupe, ’23 Dodge. They rarely beat him. He could spot a hundred models dating back to the 1910s. “It was as if I was trying to divorce myself from the presence of the people around me,” he said, “and focus myself only on the cars.”

The only adult who encouraged Hill was his aunt, Helen Grasselli, a wealthy Cleveland socialite. After divorcing her husband, a successful chemical manufacturer, she came west and settled in a house down the block from her sister. Helen had no children of her own, so she doted on her niece and nephews, buying them gifts and taking them on vacations in Miami. She favored Phil in particular, in part because she shared his fascination with cars. She let him sit on her lap and handle the oversized wooden steering wheel of her Pierce-Arrow LeBaron Convertible Town Cabriolet as they cruised empty canyon roads. It was a car of stately luxury with an outdoor seat for chauffeurs and a wood-lined passenger cabin furnished with a lamb’s wool rug and a beaverskin lap robe. “Phil was in awe of that car,” said George Hearst Jr., grandson of William Randolph Hearst and a classmate of Hill’s at the Hollywood Military Academy. “We all we

re.”

Before the development of automatic transmissions and power steering, driving was an act of physical athleticism. Climbing the Sepulveda Pass through the Santa Monica Mountains one day, Helen grew impatient as Louis, the chauffeur, ground through a ponderous series of ill-timed gearshifts. She shoved him aside and took the wheel. When Hill was twelve, he and Helen spotted a black Model T Ford in a used car lot while walking down Figueroa Street in downtown Los Angeles. “It had only 8,000 miles on it and everything was original,” he later said, “but they wanted an outlandish price for it—$40.” His aunt bought it for him and arranged for its delivery that evening. “I peeled back the curtains and there it was, shuddering back and forth in the street below, with that familiar whine of the planetary box, and unmistakable sound in low and reverse,” he said. “The salesman told me, ‘Now, you get low by pushing the left-hand pedal down, high by letting it out. The middle pedal is for reverse and the throttle is on the right side of the steering column. Have you got that, boy?’ ”

Hill’s father disapproved, and he ordered his son to stay off public roads. Fortunately for Hill, his friend George Hearst Jr. owned a slightly later version, the Model A. The boys drove the private roads of the Hearst estate in Santa Monica Canyon, and they staged races on a quarter-mile horse track on the property, skidding their way around the dirt oval.

“I learned a hell of a lot about the dynamics of cornering from that old Model T,” Hill said. Even then he knew how to pull back from the edge of recklessness. “I was enthralled with cars and power and speed, but I already had a certain saving caution. I did not, for example, ‘bicycle’ that Model T—in other words, corner it on two wheels, as some characters I knew often did with their cars.”

Limit, The

Limit, The